The motion of a dissonant chord moving to a consonant chord is called a cadence or resolution.

This post will define and analyze the strongest and most common cadences in music and provide examples of each one.

Harmonic and Melodic Tendencies

The tension heard in a dissonant chord is resolved when it moves to a consonant chord because the notes contained in the dissonant chord tend to pull strongly to the notes in the consonant chord.

The two reasons the notes in a dissonant chord pull strongly to the notes in a consonant chord are:

- Any given note tends to pull strongest to the note located half step above or below it and next strongest to the note located a whole step above or below it.

- In the strongest cadences, each voice (or note) in the dissonant chord is located a half step or a whole step away from a voice (or note) in the consonant chord.

Cadences

The strongest and most common cadences are defined and analyzed below.

The Authentic Cadence (V7 – I)

The motion of a dominant seventh chord moving to the tonic chord a perfect fifth below it (written V7 – I) is called an authentic cadence, which is the strongest chord movement in music.

For example, the sound of a G7 chord moving to a C major chord is the authentic cadence in the key of C major (fig.1).

Fig.1

Analysis of the V7 – I Authentic Cadence

The V7 chord in any given key pulls strongly to the tonic I chord a perfect fifth below it because in a dominant seventh chord:

- The third note pulls strongly to the root note in the tonic chord a half step above it — B to C (fig.2a).

- The flatted seventh note pulls strongly to the third note in the tonic chord a half step below it — F to E (fig. 2b).

- The fifth note pulls to the root note in the tonic chord a whole step below it — D to C (fig.2c).

Fig.2

The V7(b9) – I Cadence

One reason to alter a dominant seventh chord is to create greater dissonance within it, intensifying the authentic cadence.

The V7(b9) – I cadence is especially intense because the notes in the more dissonant, altered dominant chord pull even stronger to the notes in the tonic chord, than do the notes in the unaltered dominant chord.

For example, the sound of a G7(b9) moving to a C major chord is more dramatic than the sound of a G7 chord moving to the same C major chord (fig.3).

Fig.3

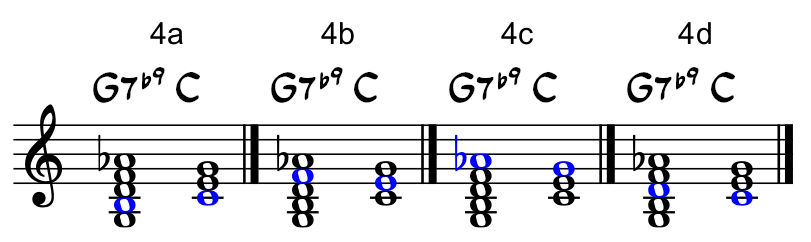

Analysis of the V7(b9) Cadence

The V7(b9) chord in any given key pulls strongly to the tonic I chord a perfect fifth below it because in a V7(b9) chord:

- The third note pulls strongly to the root note in the tonic chord a half step above it — B to C (fig.4a).

- The flatted seventh note pulls strongly to the third note in the tonic chord a half step below it — F to E (fig.4b).

- The flatted ninth note pulls strongly to the fifth note in the tonic chord located a half step below it — Ab to G (fig.4c).

- The fifth note pulls to the root note in the tonic chord a whole step below it — D to C (fig.4d).

Fig.4

The vii°7 – I Cadence

The motion of a diminished seventh chord moving to the tonic I chord a half step above it (written vii°7 – I) is similar to the authentic cadence, but the resolution is not quite as intense.

For example, the sound of a B°7 chord moving to a C major chord a half step above it provides a strong resolution. (fig.5).

Fig.5

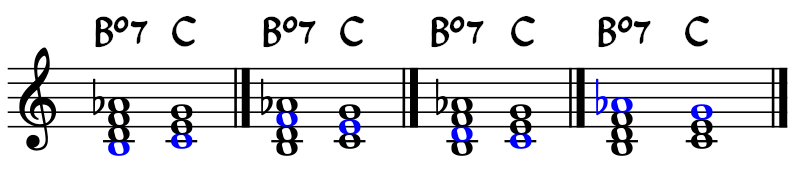

Analysis of the vii°7 – I Cadence

The vii°7 chord in any given key pulls strongly to the tonic I chord a half step above it because in a diminished seventh chord:

- The root note pulls strongly to the root note in the tonic chord a half step above it — B to C (fig.6a).

- The flatted fifth note pulls strongly to the third note in the tonic chord a half step below it — F to E (fig.6b).

- The flatted third note pulls to the root note in the tonic chord a whole step below it — D to C (fig.6c).

- The double flatted seventh note pulls strongly to the fifth note in the tonic chord a half step below it — Ab to G (fig.6d).

Fig.6

The bII7- I Cadence

The motion of a dominant seventh chord moving to the tonic I chord a half step below it (written bII7 – I) is another strong cadence.

For example, a the sound of a Db7 chord moving to a C major chord a half step below it provides a strong resolution (fig.7).

Fig.7

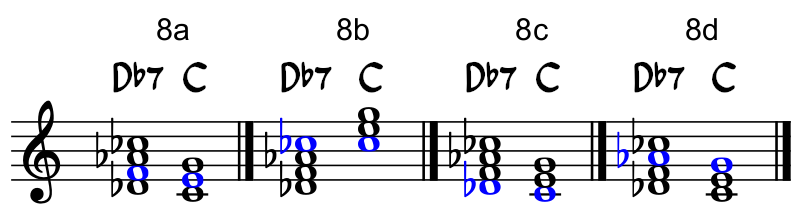

Analysis of the bII7 – I Cadence

The bII7 chord in any given key pulls strongly to the tonic I chord a half step below it because in the bII7 chord:

- The third note pulls strongly to the third note in the tonic chord a half step below it — F to E (fig.8a).

- The flatted seventh note pulls strongly to the root note in the tonic chord a half step above it — Cb to C (fig.8b).

- The root note pulls strongly to the root note in the tonic chord a half step below it — Db to C (fig.8c).

- The fifth note pulls strongly to the fifth note in the tonic chord a half step below it — Ab to G (fig.8d).

Fig.8

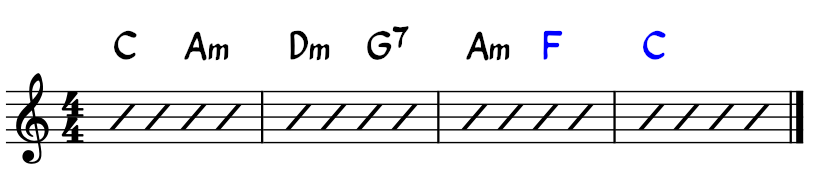

The Deceptive Cadence (V7 – vi)

A deceptive cadence is one in which the V7 chord does not resolve to the tonic I chord but moves to a different chord — usually the vi chord — which is a weaker resolution.

For example, the chord progression in fig.9 is in the key of C major and contains a G7 chord. Instead of moving to the tonic chord, the G7 moves to an Am chord instead.

Fig.9

The Plagal Cadence (IV – I)

The motion of the IV chord in any given key moving to the I chord is called a plagal cadence, which is also a weaker cadence, but a very common one.

The movement of the F major chord moving to the C major chord at the end of the progression in fig.9 is an example of a plagal cadence.

The progression is reprinted in fig.10 with the plagal cadence highlighted in blue.

Fig.10

Relationships Between the Dissonant Chords

The reason that various dissonant chords pull strongly to the same consonant chord is that the dissonant chords have many notes in common.

The V7, V7(b9), vii°7 and bII7 chords in any given key share many of the notes that pull strongly to the notes in the tonic I chord.

The four chords moving to the tonic chord all provide similar resolutions with each providing its own unique color or flavor.

Related Posts

Related posts include: