In tonal music, melodies and harmonies are based on a central (or primary) pitch, called the tonic. All of the other notes in the music are viewed in relation to this central pitch.

The key center (or tonal center) of a piece of music identifies the tonic note along with the type of scale and related diatonic chords being used in the music.

Identifying the Key Center

In some music the tonal center is easily identifiable.

For example:

- If a song or a section of a song revolves around an A note (and/or an Am chord) and primarily uses the notes in an A minor scale, the song is said to be in the key of A minor.

- If a song or a section of a song revolves around a G note (and/or a G major chord) and primarily uses the notes in a G major scale, the music is said to be in the key of G major.

In the two examples above the key center is clear.

But the key center of a song or a section of a song is not always clear; oftentimes it is a little (or a lot) more ambiguous.

Fortunately, there are a few clues we can look for to help us identify the key center of a piece of music.

Key Signature

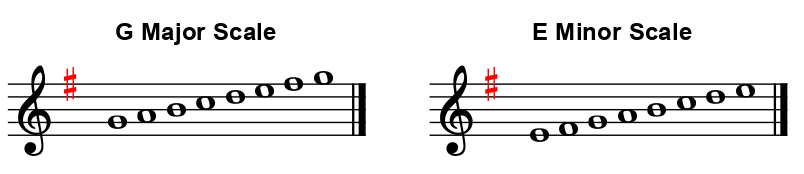

The first clue is the song’s key signature.

The key signature indicates the sharps or flats (if any) to be applied in all octaves throughout a piece of music and is located at the beginning of the music, between the clef and the time signature (fig.1, highlighted in red).

Fig.1

The key signature relates to the major or minor scale that is the basis for the song, so the key signature is a strong indicator of its key center.

Relative Major and Minor Scales

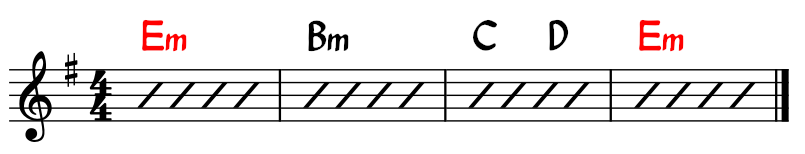

But each key signature corresponds to two scales, a major scale and its relative minor scale that shares the same notes.

For example, a key signature containing one sharp (F#) corresponds to a G major scale and an E minor scale (fig.2).

Fig.2

Shared Key Signatures

The two related scales can even be written using the same key signature (fig.3, highlighted in red).

Fig.3

So a song’s key signature will give us an indication as to its key center but will not tell us definitively. For that, we have to look at (or listen to) the music.

The Tonic Chord

To determine the key center of a song with one sharp (F#) in the key signature, we have to determine if the primary tonality is G major or E minor.

One way to make this determination is by trying to identify the tonic (or primary) note or chord being used in the music.

The tonic note or chord will often be the first and/or last note or chord in the song (but doesn’t have to be) and it’s the note or chord on which the music comes to settle or rest.

Key of G Major

If the music is centered on a G major chord, then the song or chord progression is likely in the key of G major.

The progression in fig.4 is in the key of G major. It begins and ends on a G major chord and the other chords in the progression are also diatonic to the key of G major.

Fig.4

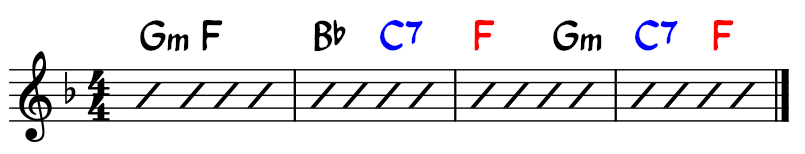

The Key of E Minor

If the music is centered on an Em chord, then the song or chord progression is likely in the key of E minor.

The progression in fig.5 is in the key of E minor. It begins and ends on an Em chord and the other chords in the progression are also diatonic to the key of E minor.

Fig.5

The Dominant Seventh Chord

As there is only one dominant seventh chord diatonic to each major key, its presence in a major key song or chord progression is another strong indicator of the music’s key center, especially when it’s followed by the tonic chord in that same key.

For example, the progression in fig.6 contains a C7 chord — which is only diatonic to the key of F major — followed by the tonic chord in F major twice.

The other chords in the progression are also diatonic to the key of F major and the key signature corresponds to that key. So the progression in fig.6 is in the key of F major.

Fig.6

The Cycle of Dominants

There are 12 key signatures, each corresponding to one major key and its relative minor key.

The cycle of dominants (also called the cycle of fifths and the circle of fifths) shows the 12 key signatures in a particular order, around a circle (fig.7).

Fig.7

The letters on the outside of the circle represent the root notes of the 12 major scales or 12 major keys.

The chord symbols on the interior of the circle represent the 12 minor scales or 12 minor keys.

The key signatures inside the circle tell us which notes are sharp or flat (if any) in each major key and its relative minor key.

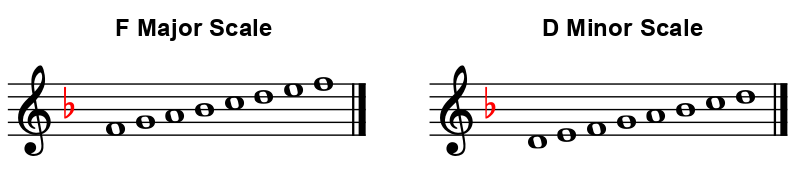

The Keys of F Major and D Minor

For example, the cycle of dominants tells us that the key of F major and its relative minor key, D minor, both contain one flat (Bb) in their key signatures (fig.8).

Fig.8

The Keys of Eb Major and C Minor

The cycle of dominants also tells us that the key of Eb major and its relative minor key, C minor, both contain three flats (Bb, Eb and Ab) in their key signatures (fig.9).

Fig.9

Cycle of Dominants Arrangement

The sharps and flats in each key signature are written in a specific order that never changes. The circle is a visual aid to help us remember the order of the keys and their respective sharps and flats.

There are six key signatures containing sharps, six containing flats and one containing no sharps or flats. The Gb and F# major scales are enharmonic equivalents (the same scale with the notes spelled differently).

Moving Clockwise Around the Cycle

Starting at the top and moving clockwise around the circle, the number of sharps in each sharp key increases by one (and each key contains the previous key’s sharps) and the number of flats in each flat key decreases by one.

As we progress around the circle, the keys move in intervals of fifths, meaning that each successive key starts five scale steps higher than the previous one.

For example, if we start at the top of the circle, on the C:

- C to G is five steps (C, D, E, F, G).

- G to D is five steps (G, A, B, C, D).

- D to A is five steps (D, E, F, G, A).

This movement in intervals of fifths continues as we move clockwise around the cycle.

Moving Counterclockwise Around the Cycle

Starting at the top and moving counterclockwise around the circle, the number of flats in each flat key increases by one (and includes the previous key’s flats) and the number of sharps in each sharp key decreases by one.

As we progress around the circle, the keys move in intervals of fourths, meaning that each key starts four scale steps higher than the previous one.

For example, if we start at the top of the circle, on the C:

- C to F is four steps (C, D, E, F).

- F to Bb is four steps (F, G, A, Bb).

- Bb to Eb is four steps (Bb, C, D, Eb).

This movement in intervals of fourths continues as we move counterclockwise around the cycle.

Related Posts

Related posts include: